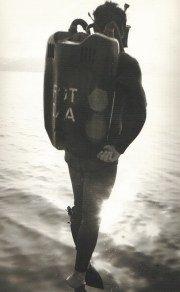

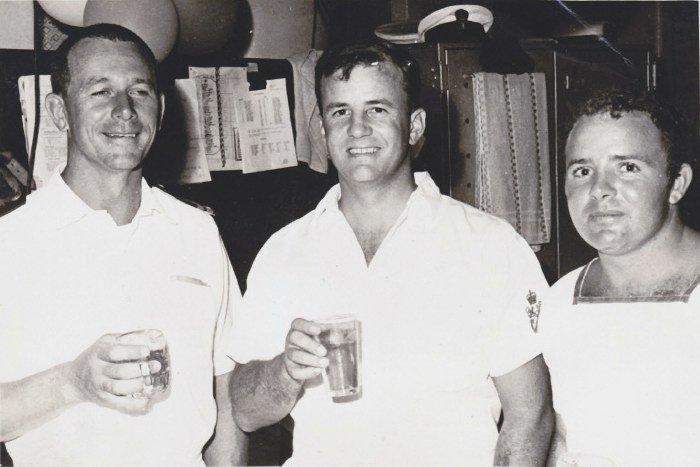

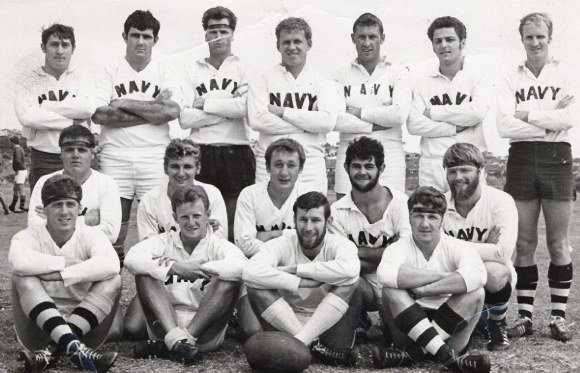

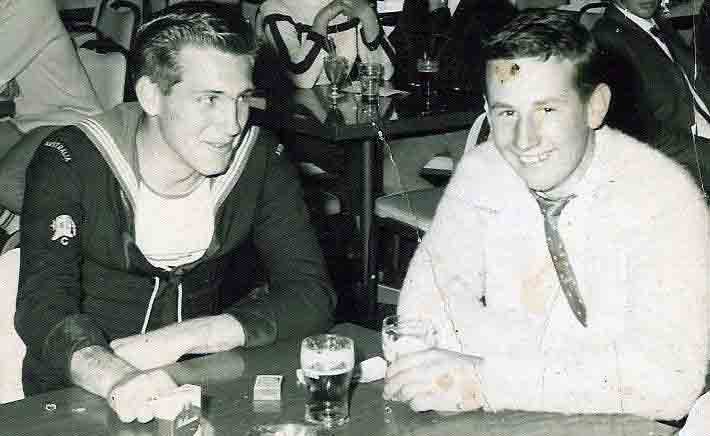

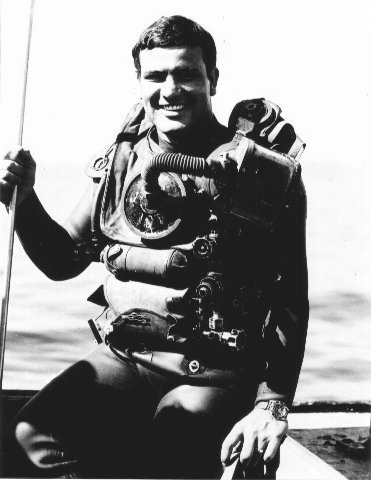

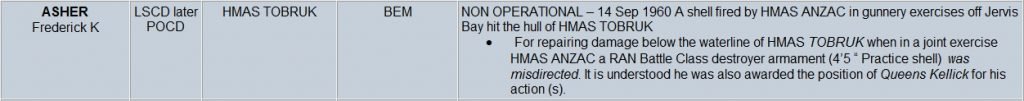

POCD Kevin (Smiley) Asher.

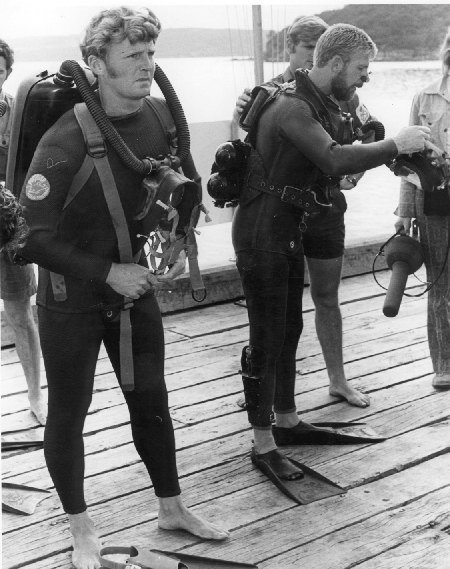

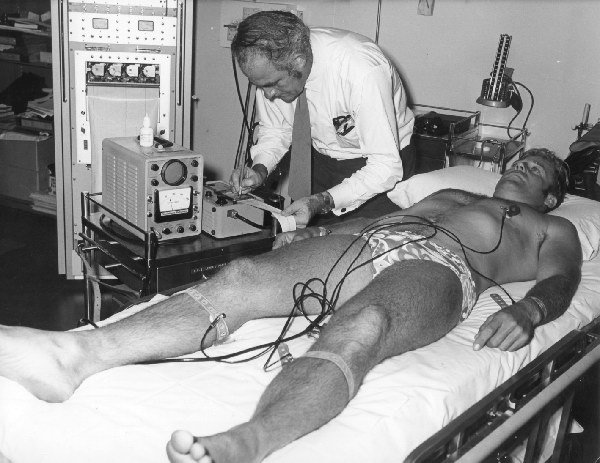

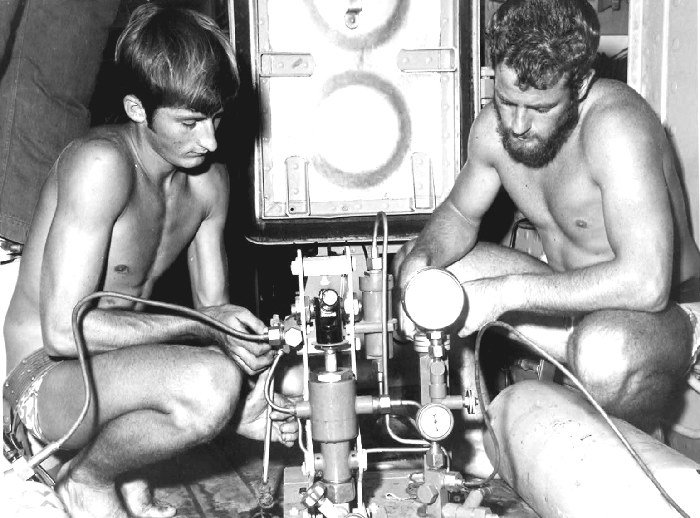

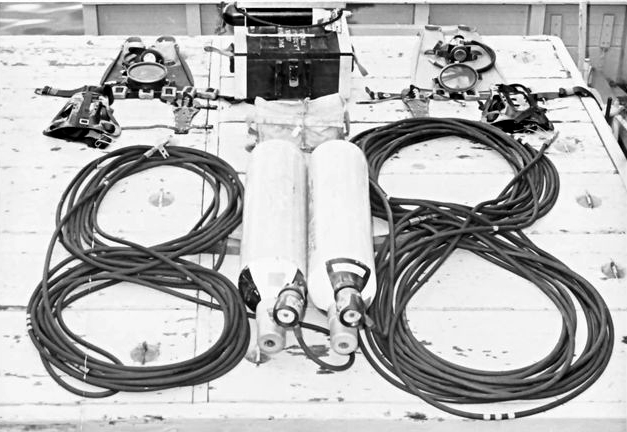

“Quote from the OIC Diving of the time. ‘These men dived on outdated equipment, equipment that was never approved officially using non RAN accepted decompression tables that had been known to at least injure if not kill people to a depth that had not been worked in before by the RAN diving branch. Not for glory they did the job but because that is the ethos of the diving branch.’ end of quote. The Sea King was rumoured to fly out of the sky because of a five cent O ring malfunction in the rotor head. The Navy wanted it back so they could get a free Sea King. The chopper was in two hundred and forty five feet of water. The task of putting a location line on the chopper was carried out by Mark Latimer. He managed to lasso the chopper from 180 feet because the gas he was using was toxic in excess of that depth so he could not go to 245 feet. The bowline bend I and others observed on the chopper end of the rope was a masterful effort. The advanced course of 1975 was tasked with the job. Brian Furner and Larry Digney suffered decompression sickness in preparing for the job. Graham Miller suffered from nitrogen narcosis on the job. Chris Balven also suffered decompression sickness on the job. In my case, Eric McKenzie, I dived on the task in the following way. A very large shackle was attached to a very long heavy duty line. I hung onto the shackle at the surface. Phil Narramore & Larry Digney let the shackle go & paid out the rope. One minute to the bottom, not the four minutes it should have taken. I dragged the shackle to the chopper, up & over the chopper to the rotor head. I took the shackle off the rope & fed the rope around the rotor head under the rotor. Two turns of rope then I put the shackle back on. I got the call up. Sixteen minutes had elapsed. I then had a breathing restriction which meant I was on emergency. I slowed down my breathing. I moused the shackle. I checked the job. I turned on my emergency. I tried to take a good breath. Not a good idea. No air left. I swam over to the dive line (2.5 knot current). I started the ascent. As free ascents go, it was a good free ascent. Max Dennis was waiting for me at 90 feet with another cylinder of air. He looked lovely. Several hours later I exited the water. A high speed dash to HMAS STALWART in the rubber duck. A crane ride inboard. A quick warm shower. Then the bends hit. In the recompression chamber for an untold amount of hours. Nev Moffit (medic) was happy to see me. Other divers were having a light hearted shot at me – Phil Narramore had promised them the afternoon off, not to be. So ended another day on the Sea King job.”

– Eric McKenzie.

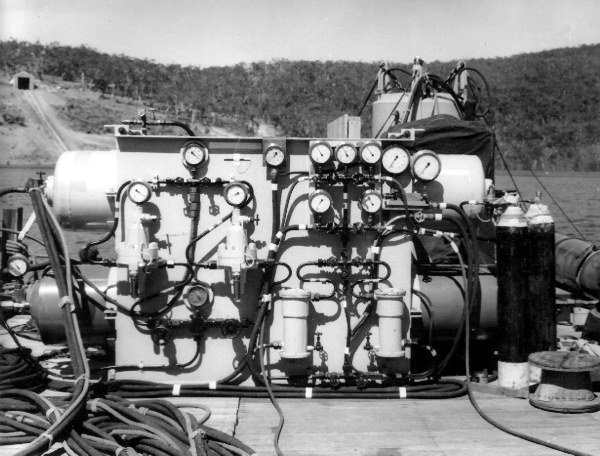

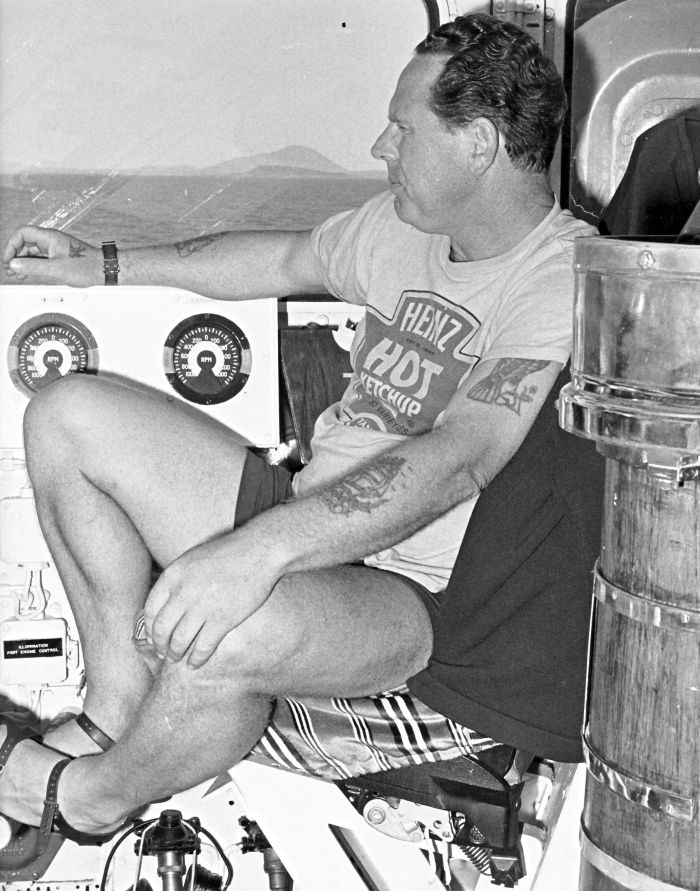

The RAN operated a torpedo range at Taylors Point from 1941 to 1983, to test the firing ability and the range of torpedoes before they were issued to submarines. The building was built specifically as a torpedo training facility with a torpedo carrying crane and a ground floor railway providing optimum ability for torpedos to be transported to the firing station.

5059 torpedoes in total were fired from Taylors Point up Pittwater. Navy launches cleared small craft from the firing area, a large red warning flag was unfurled from the firing shed and a siren sounded. Three pontoons were positioned in the water from which the speed and accuracy of the torpedo’s course were registered and relayed back in the firing tower. The torpedoes were then retrieved by a patrolling launch. In 1983 the firing station and outer wharf were removed and the centre was converted for diving training for the RAN Diving School located at HMAS PENGUIN.

Since 1984 the Pittwater Annex has been an integral part of RAN diver training. Initial training and initial dives are conducted at HMAS PENGUIN prior to the course relocating to the Pittwater Annex for more advanced training.

Today the Pittwater Annex is used for Maritime Tactical Operations, Mine Countermeasures and conduct of the Clearance Diving Acceptance Test (CDAT). The MCM and MTO phases are seven weeks each and these are conducted twice a year at Pittwater. CDAT is ten days with six days conducted at Pittwater.

Sources:

Godden Mackay Logan HMAS PENGUIN INtial Heritage and Environment Review – Draft Report 2008

Nan Bosler, The Fascinating history of Pittwater, Part two. 1998

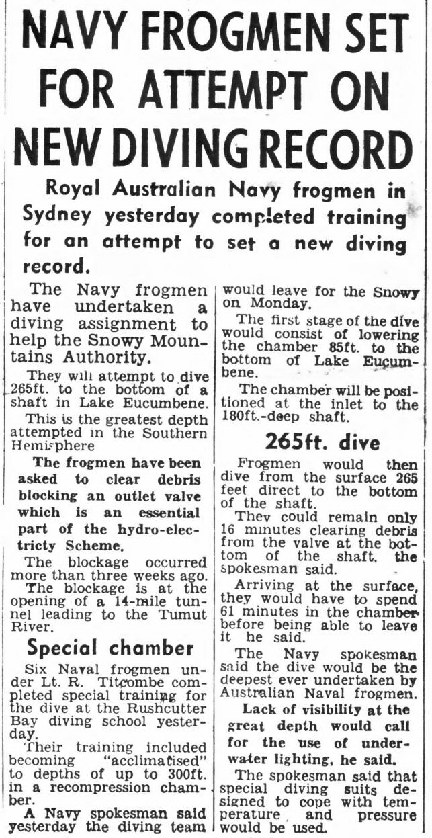

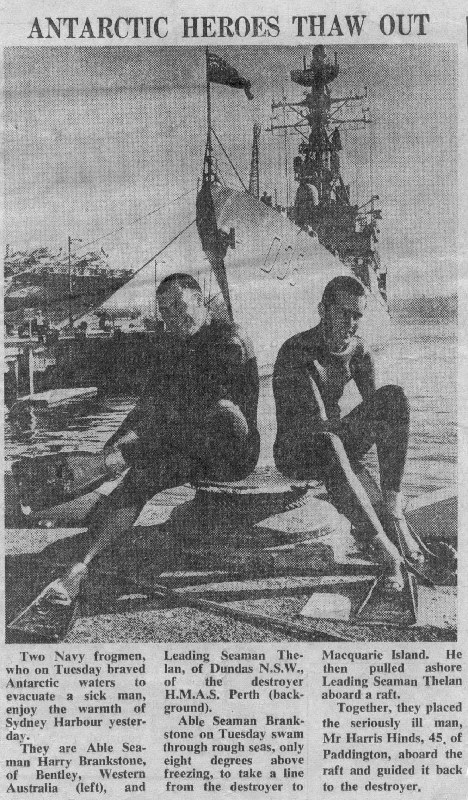

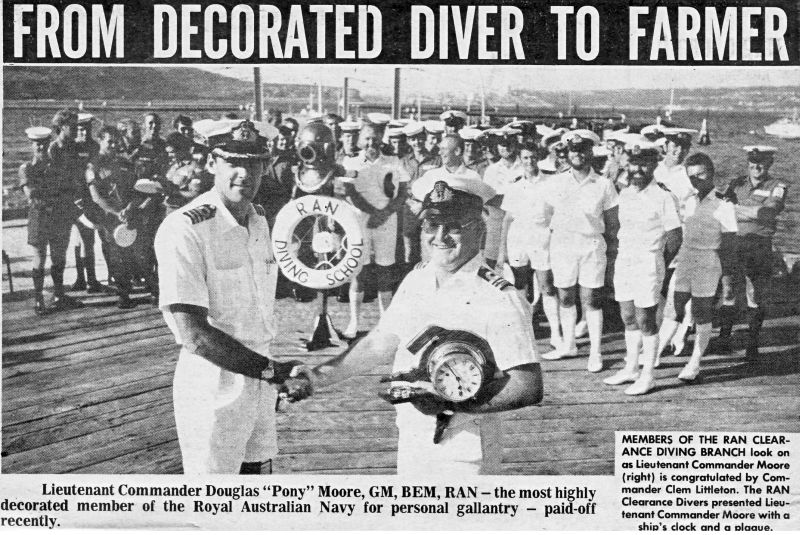

Extract from the Navy News. Courtesy of the Navy News. Page 16. January 17, 1975

(Eric McKenzie. ex CPOCD.)

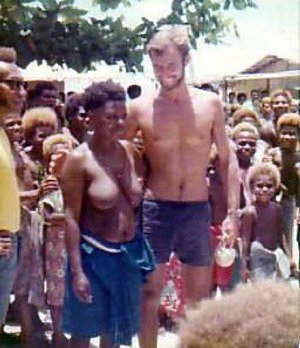

Cyclone Tracey Christmas 1974.

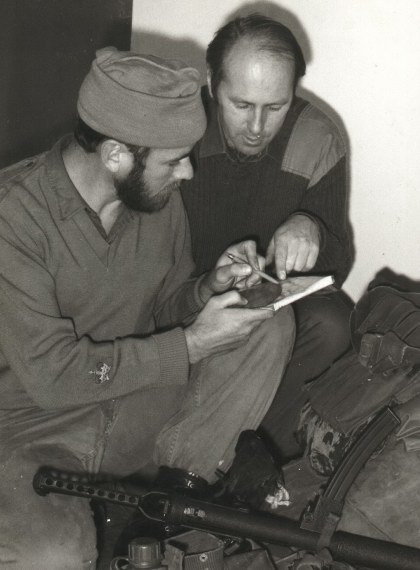

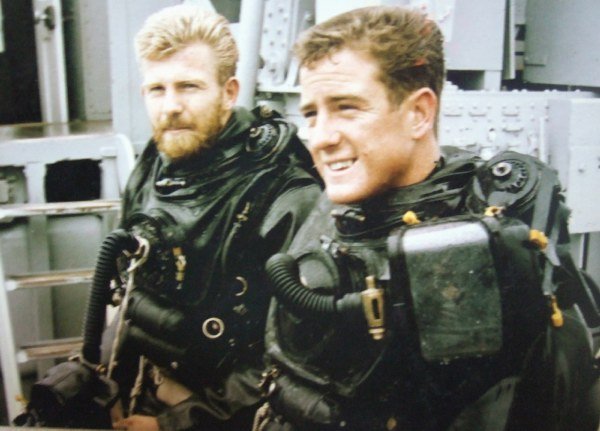

Clearance Diving Team One in Darwin

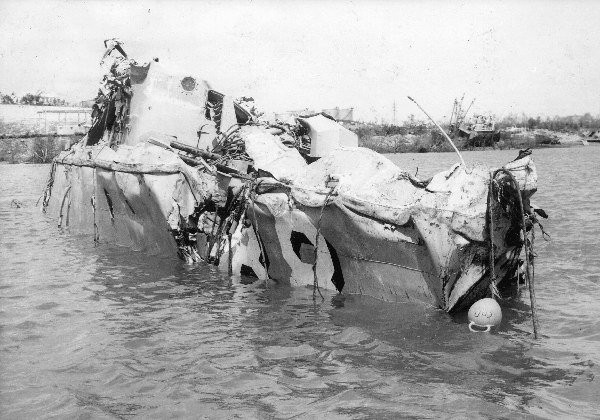

Sunken Patrol Boat salvaged by RAN divers.

“The ingenuity of the RAN’s Clearance Diving Team Number One led to the salvage of the Patrol Boat, HMAS ARROW, which sunk after hitting Darwin’s Stokes Hill Wharf during cyclone Tracy on Christmas Day.

The diver’s success came after 20 days of hazardous work, and an early setback when a cable attached to ARROW snapped. ARROW was finally raised from the harbour floor, dragged underwater away from the wharf and beached nearby to allow inspection and repairs to be carried out. (Refer to salvage photo.)

They spent 12 days fixing hawsers to strong points on the sunken vessel. They had to swim through the twisted wreckage trailing the hawsers behind them. They then connected the other ends of the hawser to two pontoons moored forward and aft of Arrow’s position. The big day was Saturday, January 11, and as the tide rose so did the pontoons. They acted like big floating cranes to lift ARROW off the mud. This part of the operation was a complete success and ARROW floated about 11 feet above the bottom, but still submerged.

The next part of the operation was the difficult one – to pull the wreck away from the wharf into shallow water to beach it. Everything was going well……but suddenly a cable parted on the bow pontoon. The bow of ARROW sunk back into the mud. (no mention of imploding winch drums). But the tug and a civilian trawler pulled the other pontoon…and ARROW began to move. The divers then relashed the Arrow’s bow to the other pontoon and on Monday, January 13, succeeded in their goal and beached the patrol boat the following day.

Interested observers at the salvage operations were the Naval Officer Commanding North Australia, CAPT Eric Johnston and the Fleet Commander, RADM D.C.Wells. The first task in the ARROW salvage had been to find a pontoon. The only one available had been beached and first had to be salvaged before the ARROW work could commence. In attaching strong points of the ARROW to the pontoons the divers had to go down inside the sunken vessel and pull the wires through the scuttles. As the OIC of the team LEUT Dave Ramsden said: “it was not the easiest diving. The water was very murky and there were jagged pieces of metal everywhere”.

In a preliminary lift on January 7, to see what would happen, the divers secured lines to the pontoon at low tide.

As the tide rose, so did the pontoon. ARROW, attached to the pontoon, also moved a few feet-proving the divers’ theory correct. “All we had to do now was consolidate this and lift her off.” Said LEUT Ramsden.

The divers then set about re-arranging the lines to the Arrow’s stern to give a better lift and brought in a second pontoon at the bows. Partial success came on January 11; ARROW was hauled up on January 13 and finally beached on January 14. The clearance divers had succeeded-again.

It was just one of the many important tasks they had undertaken after arriving on Boxing Day on only the second plane into Darwin following Tracy. (Dr Jim Cairns, Acting Prime Minister beat us. Our excuse is we had to load our own gear – Macca).

On Boxing Day everything was just as it was on Christmas Day. Two Patrol Boats, ASSAIL and ADVANCE, were alongside Stokes Hill Wharf. The divers went down into the murky black, debris-covered water to inspect the Patrol Boat hulls for damage. They found both boats had propeller and shaft problems. But both were operational, although ADVANCE only had one propeller.

Their next task: FIND ARROW.

They found it wedged firmly beneath the pylons on the outer corner of Stokes Hill Wharf.

The fourth patrol boat, ATTACK, had been driven up on the foreshore during the cyclone. There were two holes visible in the hull but they were patched up sufficiently for the Patrol Boat to be refloated. She was refloated that day but immediately developed a severe leak. So down the divers went again. They discovered a third hole.

The clearance divers worked fairly much to the same daily pattern although as LEUT Ramsden said-“I didn’t realize it until I looked at the log.”

Every day their main tasks seemed to be to give assistance to vessels which had survived the cyclone, to locate wrecks in the hope of finding missing bodies, and clearing the wharf faces so ships could come alongside.

They also worked on general harbour duties, such as checking fuel valves and removing pieces of metal from the wharves and water.

LEUT Ramsden’s notes for December 29 say: “Diving conditions bad-black as pitch under fifteen feet, much jagged metal – no place for divers.”

But they kept on, day after day, diving, diving and still more diving.

Their day never shorter than twelve hours. Their job-dangerous and highly important.”